When Your Rabbi is a Catholic Tenor: Lessons of Teshuva Through Music

Note: jLab is for blog posts about creative, fun, or interesting Jewish or congregation-related topics. To submit a post, you must be a member of our congregation, and the topic must be Jew-ish, related to our congregation or the wider Jewish community. If you have something to share, please submit it here.

By: Leslea Haravon Collins

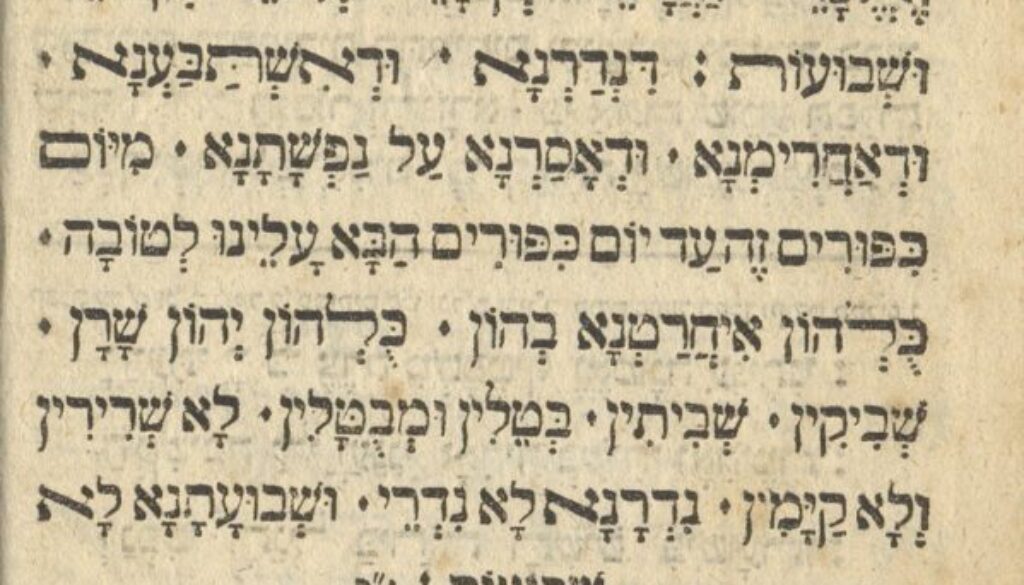

The angels are dismayed. They are seized by fear and trembling as they proclaim: Behold the Day of Judgment! –from the High Holy Day liturgy

The unwritten part of this passage is, of course, that these angels were asked by their rabbi to daven Kol Nidre, a piece that instils fear and trembling in even the best of singers/angels. And – trust me here – I am neither of these.

Kol Nidre is a powerful and moving piece for congregants to listen to and chant along with, one that may invoke memories of loved ones in the distant past as well as our own reckonings with life’s fragility. For the chazzan (singer), this piece packs all of those regular punches, together with the intimidating desire to deliver to her listeners all a meaningful experience of kavanah, or soulfulness and intention (enter the “fear” part). Additionally, and not inconsequentially, the piece is a musical journey through an impossibly large vocal range, odd intervals, and tricky rhythms –a recipe for “trembling” for the singer if ever there was one.

As often as politely possible, I hide from this piece. I find as many excuses as I can to say “no thanks” to the Rabbi’s kind and humbling yearly request to sing it – not enough prep time, too much else going on, someone else can do it better (this last one is always true), etc. This year, however, I said yes.

I said yes because this time is so fraught; if we are all dealing with life and death issues in both health and financial arenas, then surely I can be a mensch and take this piece on. So, with the requisite fear and trembling, I began my Kol Nidre journey this summer.

In addition to practicing vocal exercises daily, preparing Musaf prayers, and learning ever more about the Yamim Noraim (days of awe) with textual study, I am taking lessons from a vocal instructor – the fabulous Brian Manternach, introduced to me by a certain undergraduate at the University of Utah (see his inspiring (even and especially if you don’t sing) Ted Talk here.

I don’t know much about music anymore, although I used to. I can read it some, took (and loved) music theory years ago, played instruments, and studied voice in college. But life took over and I became a mom, a scholar, a money-maker (not much, but still!), a laundry-doer, a dish-washer and dinner-maker. You know how it goes. Brian brings me back to who I was when “singer” was part of my identity. Talk about days of remembrance!

Learning with Brian, I confessed to him the weight, not only of the High Holy Days in general (he’s Catholic, so needed a bit of a primer), but of Kol Nidre in particular. As both a professional and a liturgical singer, Brian could certainly understand how a piece might be intimidating.

At one point, he coached me to “bring the piece home.” Even without knowing about teshuva, the “returning” to ourselves that we are expected to do during this time in our religious cycle, Brian gave me the words -and the image – to use when thinking about this music. “There is no pressure to deliver exactly what you think they want,” he told me. “the piece is you putting yourself – as you are – into the music.”

His wise encouragement reminded me immediately of the Talmudic story of how Reb Zusha, on his deathbed, told his students that God would ask him, in the world to come, not “why were you not more like Moses?” but “why were you not more like Reb Zusha?” Of course, I promptly told this story to Brian. We went over our lesson time. Again.

And yesterday, another nugget of wisdom from Brian. We were talking about another of the many musical difficulties of Kol Nidre – that many of the notes hover right around the “break” in the voice.

For those unfamiliar with the vagaries of singing, the voice has a lower range (called colloquially the “chest” voice) and an upper one (known as the “head” voice). While it’s fairly easy to hang around vocally in one or the other of these ranges, switching between the two and singing right at the “break” (the common term for the notes right around where they switch) are difficult musical tasks (assuming that you want your voice to sound good, that is).

As he talked about how to negotiate this vocal “break,” I started to wonder if perhaps Kol Nidre is written this way on purpose – what if the Chazzan is encouraged – maybe even expected – to “break?” Given that Yom Kippur is all about fragility, vulnerability, human imperfection, and the inescapable nature of our ultimate end, wouldn’t it makes sense that we all should “hover around the break” in our voices, and in our lives, on this day of awe?

I certainly am breaking a lot right now, and not just in my voice lessons. I broke when the derecho came through Iowa. I break as friends get sick with Covid. I break as our government puts us in harm’s way. I break as the ugly racial truths of our country are exposed. I break as I see relationships shatter, the climate change, the storms surge, the politicians lie, and the hope of young people wane.

Brian was teaching me that the “correct” term for the vocal “break” is actually the more elegant, delicate and of course Italian “passaggio,” meaning “transition.” He then smiled conspiratorially, the glint in his eye evident even over zoom: “But we all know it’s really a ‘break,’” he said.

Yes, Brian, we do. And not just in Kol Nidre. All transitions are really breaks. All breaks are really transitions. I am learning this from you and from my study of the High Holy Days.

Rabbi Menachem Mendel of Kotzk famously said “there is nothing so whole as a broken heart.” Maybe a broken voice is somehow whole, too.

I will break during Kol Nidre. I hope that you will break with me. And maybe, in our brokenness, we can heal, start again, and keep singing.