Alone but not Lonely

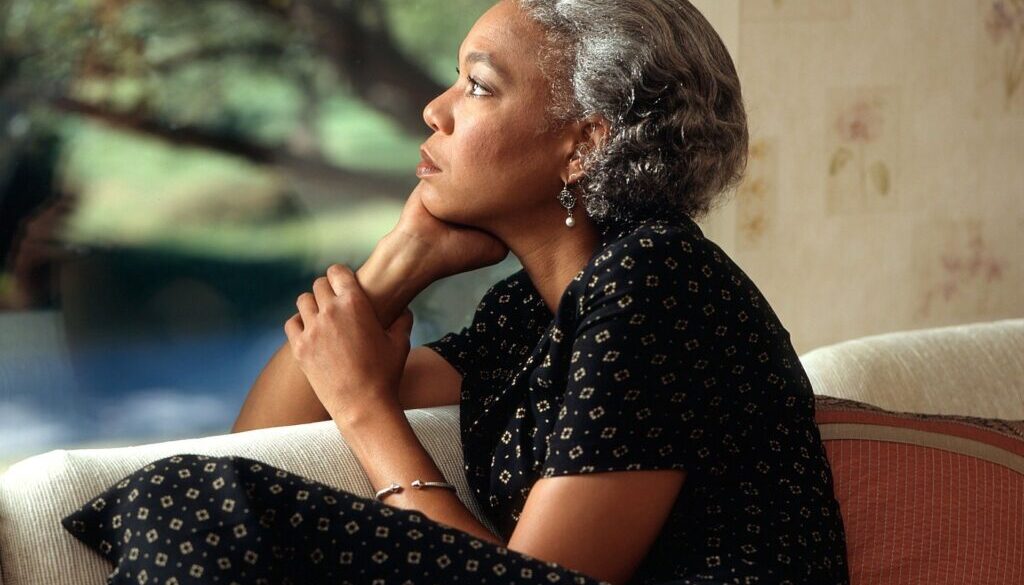

It gets lonely, doesn’t it? Being shut in the way so many of us are.

I had commissioned a friend to make some cloth masks for my family and she did a wonderful job (Star Wars-patterned fabric for the boy and unicorns for the girl). She did a curbside drop-off with the masks in a paper bag and with mini loaves of banana bread thrown in for good measure. We talked to them; us from our porch, they in the drive-way, and in a complicated, socially-distanced way, I was able to offer the family slices of homemade caraway seed cake. It was the first in-person human contact – even which socially-distancing with over 15 feet between us – that my family had had in almost two months.

I am sure you can relate: it’s been a very lonely two months. Considering we are blessed to have each other’s company, I cannot imagine how much harder it is for others less fortunate to be in a strong family unit like us.

Still, this is our lot and it may be our lot for the foreseeable future and all of us involved in the project of building sacred community can turn our thoughts to not just the medical implications of this plague but its social consequences too. The spike in mental health issues; the vulnerability many of us feel, the loneliness, the anxiety, the paranoia about catching the novel Coronavirus, the deprivation of normal human contact. These are not little things just because they are private things. Each of us is waging a war, fighting a battle. Each of us will have to contend with what this all means for our souls as well as our bodies.

This week’s Torah portion is primed towards the body. Tazria-Metzora has the running joke of being the nemesis of B’nei Mitzvah students the world over, but as you may well know by now, this season of the plague is the ultimate vindication of the Book of Leviticus. We read meticulous instructions on how to diagnose, isolate and purify. Bodies that ooze, bodies that erupt, bodies that are tinged with death amidst the great and ancient struggle to perpetuate life.

Today, I tried on my cloth mask for the first time. It is an elegant design of white and pale grey chevrons. I bent the wire to fit the contours of my nose and tied the straps behind my head. It was slightly uncomfortable and plenty discomforting. It labored my breathing and as I looked into the mirror, it was shocking to see the image of own humanity crack as part of my face became concealed. It was a more existential moment than I thought it would be. This too, is Levitical: a meticulous act meant to diagnose, isolate and purify. It is the quarantining of our countenance, binding up our smiles, containing our expressions, words, breath.

Amidst the myriad details of this week’s portion, there are two words that the Priestly text uses over and over again to signal what must be done to the human being who is, somehow, tainted: ‘lehasgir’ and ‘badad’: to ‘shut someone out’ and to be ‘isolated’ or ‘lonely’. We can look at these words as technical terms or as emotional states. One of the hidden truths of Leviticus lies not in its minutiae but in its unspoken, implicit compassion. People aren’t quarantined forever. They are reintegrated. They find healing but they also find spiritual restitution. We forget that the ordinances of Leviticus were not unusual but part of the rhythms of ancient life. There was no stigma to the measures; no judgment on the system of purity.

That is our lesson for today. We must abide by our stringent rules, but let there be no recrimination, no judgment, no cruelty. Let caution not devolve into fear. And may we think of measures, procedures and rituals that can lift the veils of our isolation and break down the walls of our loneliness. Just as there is an infrastructure for containment, let there be an infrastructure for healing, love and reintegration. There is only one guarantee in all of this, and this applies to the uncertain days of ancient times as well as our current, contemporary predicament: we need each other, more than ever.

Ken yehi ratzon.