Parashat Lech Lecha 2021

This sermon is a ‘Modern Midrash’, imagining Abraham and Sarah as iconoclasts in a contemporary setting. The sermon explores the question of Abraham’s religious genius and its potential proximity to existential madness, especially when that genius emerges out of a context of personal trauma. This is a piece of fiction and should be read as an attempt to cast new light on ancient narratives.

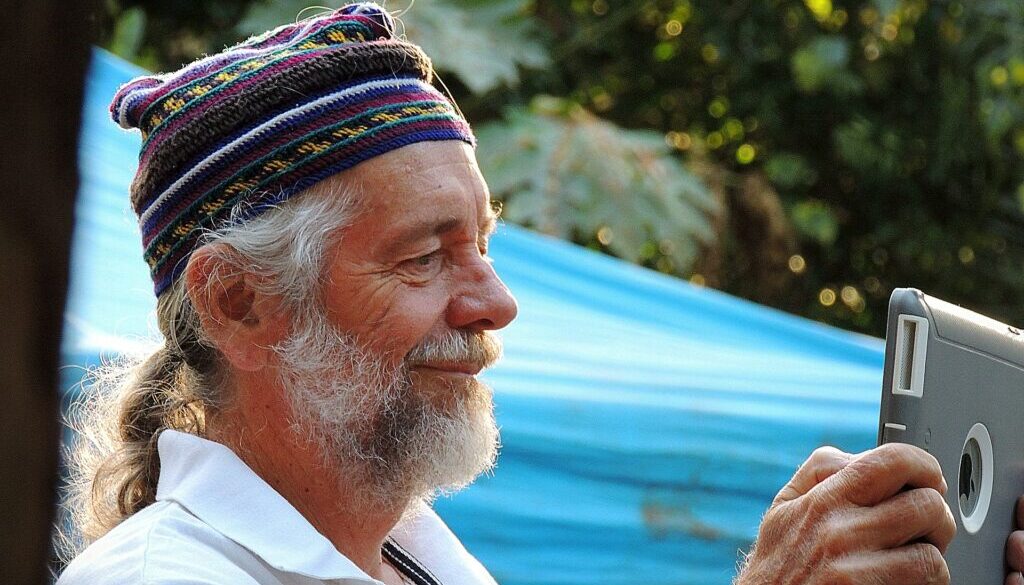

She woke up to the faint blue glare, as usual. The silk sheets and down pillows were inviting and she just wanted to burrow down deeper into them, into the comforting oblivion of sleep. But she found herself alert now, watching the old man’s face stare intently at the screen of his iPad. There was something in his inscrutable expression that she couldn’t quite place; something secretive and visionary. It exhilarated and worried her.

She shook off the blanket and achingly erected herself, her age a constant companion in her bones. ‘Avram’?

‘Hmmm…’ he hummed absentmindedly. ‘Avram? You’re up again.’ She glanced over at his tablet and he pulled it away. ‘What?’ There was an annoyed urgency in his voice.

‘Are you looking at those websites again?’

Avram scratched his disheveled beard, shifting his position as he sat up in bed.

‘Avram’, she said, her voice hoarse from sleep. ‘I worry about you. All you do is go online and look at the gods-only-know-what. You’re pulling away from me. Pulling away from all of us.’

‘I-I’. His voice faltered. ‘I’m just doing… I need to hear other perspectives. Other ideas.’

That’s what he always said. Other perspectives. It had gotten worse over the years. Every time she picked up the newspaper, he scoffed. ‘What kind of reporting goes into that? How about all of their vested interests?’, he would say. At town hall meetings, he would nudge, complain and question. People indulged this old crank; after all, his father Terach had been a successful factory owner, the largest employer in the area. The local clay was abundant and their sculptures were of export quality. Upon retirement, Avram had delegated his corporate executive duties to the Board of Directors and had increasingly pulled back from daily operations, but they had enough wealth and prestige to see them through old age. Here he found himself, in their opulent bedroom of their richly-appointed villa, in the finest neighborhood of Ur, looking at, well, things, on his iPad.

‘Avram’, Sarai started again. ‘People are starting to talk.’ She bit her lip and ran a slender hand through her grey locks. She had grown accustomed to his sadness over the years; the gravity well of childlessness pulling in the fading light of their elder years. They had tried everything; opted into every medical procedure that money could buy. Visited every accredited fertility specialist in the Crescent. Despite her haute bourgeois notions of rationalism and reservations about organized religion, she even found herself bringing offerings to the idols made in her husband’s factory. Clean lines of finely molded porcelain and skillfully sculpted marble; painted in splendid colors, with evocative, delicate faces that seemed to speak to her, if the light hit at the right angle. ‘Oh gods and goddesses’, she found herself praying, as she poured wine and oil, burned incense and fine cakes. ‘Please give me a child.’ But the statues had remained mute, and she retreated in shame, all disdain about her ancestral religion confirmed. If divine beings and scientific minds could not plant life in her, well… then what could?

That’s how it had started. With every failed IVF cycle, every pregnancy test that rendered no results, Avram buried deeper into his reading. He started picking apart peer-reviewed journals in technical language he only partially understood. He wrote endless letters to fertility specialists about this experimental treatment and that innovative intervention, meeting a wall of silent resistance. ‘Avram’, Sarai found herself pleading with him through her tears. ‘Let’s just… stop. I can’t do this anymore.’ He had held her then and she had cried bitterly, each tear a mother’s libation to futility.

Avram kept on searching. In his office with the antique hardwood desk and the polished leather futon, adorned by a polished pink marble statue of a sensuous Ishtar, all comely curves. In their gleaming designer kitchen of granite and stainless steel. In the bedroom, among lit candles and richly woven carpets. The servants whispered. It was always Avram and his computer, or tablet or smartphone. In his head, doors of perception started opening. He jotted down notes in a spindly hand in his leather-bound notebook. ‘Not digital’, he said, ‘I don’t want them to know.’

‘Are you still convinced the doctors were wrong?’ She asked him once and he had looked up with surprised bemusement. ‘The doctors? I am not looking at that anymore. Our quest for a child is hopeless. But my inquiries have led me to other places.’ Sarai arched her finely curved eyebrows. He continued. ‘Who has created the earth?’

‘Why, the god of rain, of course.’ She responded as a teacher would to a child, not quite convinced by her own argument. He huffed with exaggerated indignation.

‘And who brings the rain?’

‘The god of wind?’

‘And who brings the wind?’

‘The gods of the sun, moon and stars?’ Her voice was starting to waver. This seemed like a ridiculous proposition. They were all taught this as children of course, as Ur grew and prospered as a city-state, in the shadow of the proud Ziggurat. But now she realized that the only thing they were doing was climbing a useless chain of causality, steeped in lore and myth, girded by social convention. ‘The gods govern all’, she tried half-heartedly.

Suddenly, she saw a fire in his old eyes, a flicker of a flame that reminded her of the valiant, visionary young man he had once been. She noticed the rising of her pulse.

‘My research, Sarai… it just doesn’t make sense. All the libraries of the Crescent attest to the same, it’s true. The gods shape our world, just as above, so too below. As they bicker and fight, so do we. As they court and breed, so do we. They make the wind blow and the rain fall; but… who created the gods?’

It seemed like such a simple question, and while Sarai had been perfunctory at best in the execution of her religious duties, Avram’s question struck even her as daringly heretical. She felt her spine tingle; an excitement and anxiousness at the base of her stomach that she had not felt in many years. With a suspicious hesitation in her voice, she asked, ‘what are you implying?’

Avram grasped her hands, squeezing them. ‘Maybe there aren’t all these gods’. His eyes widened, his breath quickened. ‘Maybe there is only one god.’ The thought made Sarai dizzy; it made the universe feel so empty; this vibrant, colorful, opulent world of god-kings and priest-kings, of temples and ziggurats, of gods violent and sensual; cosmic wheels turning by their machinations; one god set against their fellow, with only the priestly class able to discern their will. It was a heady world; full of scent and color; of sacrifice and blood, of gold and stone. Like the steps of their proud Ziggurat, each and every person in Ur knew their place. They knew their place.

‘Avram, that doesn’t make any sense. Why would they teach us about the gods if there was only one? What could one god possibly do? Bring the rain and win battles?’ she scoffed. ‘Bring us wealth and children?’ Her voice was edged with bitterness. ‘This god, then, must surely be able to do it all.’

‘But that’s the thing. Perhaps the gods keep us… well, locked in. In a prison of our own minds. Have you ever wondered what’s beyond Ur?’

‘We have family in Haran’.

‘But further west still?’

‘Why would we go further west? We have everything here. Status, wealth, servants… Ur has been good to us. This is our home.’

‘But is Ur good to all of us? And is this it, then? For us to drink fine wines and feast and dance and sacrifice and entertain and live in all this splendor? We do not even have children to bequeath this to. The gods are cruel; filled with avarice. They demand the fires upon our altars, but what else do they demand?’

‘Nothing’ Sarai said cynically. ‘Isn’t that the point of the bargain? We keep our social order, and they keep theirs.’

Avram pointed a crooked, aged finger at his wife of decades. ‘Exactly.’

‘If there’s only one god, then aren’t all of us siblings? Every human being on earth? From the far reaches of the east to the seas in the west? Perhaps all that is demanded of us is not sacrifice, but righteousness. Righteous…’ his voice fell to a husky whisper. ‘And love.’

‘Righteousness and love? You were a factory owner, by the gods. You made a mean killing. Those statues sold like hotcakes and you know it. Don’t talk to me of righteousness. And certainly don’t tell me of love. The gods do many things, but love? No, they don’t love us. We are like ants to them.’

‘Perhaps I was wrong.’ He sounded wistful. ‘Perhaps all of this is wrong. Perhaps there is another way to be.’

Sarai looked at him. He seemed frail at his advanced age, but he still had that steely determination that made him fierce in business and savvy in politics. She leaned over to him and gently, softly kissed the old man’s lips, feeling his soft, bushy beard brush against her wrinkled cheek.

‘Hush now. These notions would… change… everything. We cannot speak to anyone of this, do you understand? We cannot. You and your foolish ideas.’ But for the first time, the emptiness inside of her seemed empty no longer.