D’var for Sh’mot by Linda Kerber

D’var for Sh’mot January 9, 2021

Everyone, I conclude, should have their own Parsha – one which speaks directly to them. Technically, this is not the one I would have had for my bat mitzvah. But here in Sh’mot are two sets of verses that are not in the section I just read [Exodus 3:1-6] but on moral issues that I’ve contemplated for decades,

Exodus Ch. 1:15-19. 2:1-10

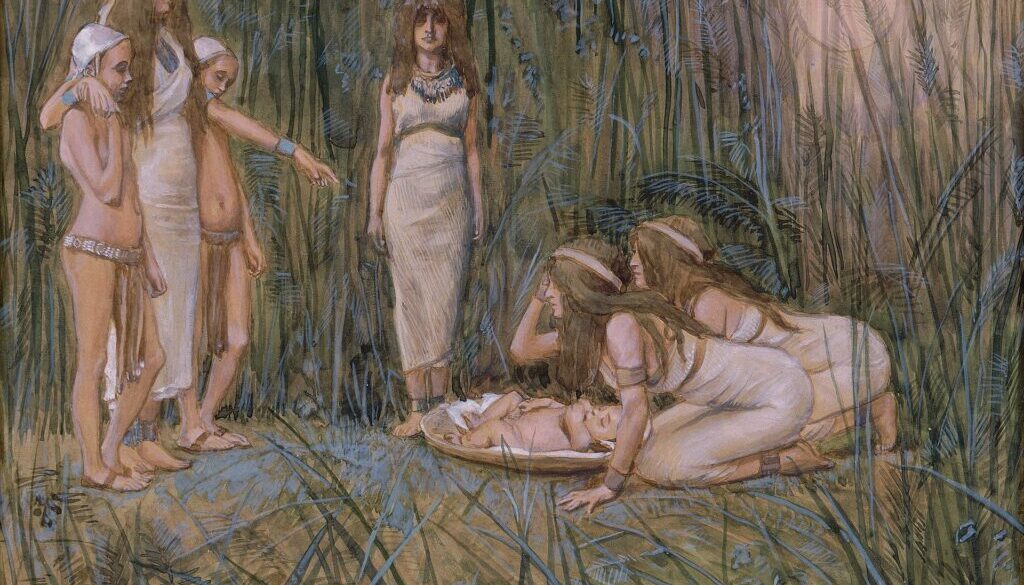

This is the story of the Hebrew midwives, and of the saving of Moses. This is the key story on which all the rest will depend . The Hebrews have been oppressed. Taskmasters have been placed over them and put them to heavy labor. The current Pharaoh – who has no memory of Joseph and all that Egyptians owe to him – treats the Hebrews as slaves, and announces that all male Hebrew infants will be killed at birth. Yet Moses will grow up, Moses will lead the Israelites out of Egypt, Moses will go up the mountain and return with the commandments, Moses will lead the Hebrews to the border of the promised land.

Like an upside-down iceberg, the weight of this whole narrative will balance on the heads of the midwives. We know their names – Shifrah and Puah. We know that they deliver the infants alive, probably the first slave rebellion in recorded history; certainly the first rebellion of women. And the weight of Jewish narrative also rests on the equally clever mother and sister of Moses (presumably Miriam), who though forced to sort-of abandon him to his fate in his basket of woven reeds, hover nearby so they can re-enter the foundational story of our people.

We do not know the name of Moses’ mother. Nor do we know the names of the thousands of parents who placed their children on the Kindertransport between 1938-1940, not knowing if they would ever see them again. And many, perhaps most, did not. In our own community is a woman whose father and uncle were on the Kindertransport. There may be more. And we do not know the names of the mothers in El Salvador and Honduras, who filled backpacks for their own children for the trek to the U.S. border, hoping, hoping for a sanctuary which they are now denied.

We are commanded by the rabbis to tell the story of the going out from Egypt, every year at the Seder. But when we read the Haggadahs that we have inherited, none of the people in these opening chapters of Exodus are in it. Not Shifrah, not Puah, not Moses’ mother, not Moses’ sister. Gone. Erased. When I asked Rabbi Jeff how this could be, he said he thought the rabbis figured everyone knew all this already, and so they filled the Haggadah with their own stories, the stories of their own arguments. Who cares? (and that’s why much of the Haggadah is so boring and we skip over it.) We do NOT tell the story of the going out from Egypt.

In modern times, we have reclaimed the women. How? Just before the American Civil War, in 1859, ten years after the formation of the American women’s suffrage movement, Thomas Wentworth Higgenson wrote “Ought Women to Learn the Alphabet?” [The Atlantic, February 1859] Those who are troubled by women’s demand for the vote, he wrote, had better begin with the alphabet, because if girls learned the alphabet they would want to learn words, and if they learned words they would read sentences, and then there would be no stopping them . (That’s the logic, by the way, behind the laws against forbidding teaching enslaved people to read.) Reform Jews started teaching girls Hebrew, and many of them could read the Torah, and they could learn about the midwives. And Jewish feminists of the 1960s made a lot of Good Trouble – as John Lewis taught us to call it– and they called out the names of Shifrah and Puah andMiriam, and they added an orange to the seder plate.

II.

Exodus Ch. 2, verses 15-22

As an adult, Moses gets in trouble and, fearing for his life, flees to the land of Midian. He protects the 7 daughters [magical number?] of Reuel, the priest of Midian, from an attack by shepherds who are preventing them from drawing water for their sheep. Reuel sends for Moses, to thank him, and shelters Moses and “gave Moses his daughter Zipporah as wife.” [note gives as unproblematic; we will discuss this another time].

And Moses names him Gershom, “for he said, ‘I have been a stranger in a strange land.” [Notes to this passage translate Ger Shom as “a stranger there.” or “an alien there”]

The call to care for the stranger punctuates the Torah throughout. Rabbi Jeff tells me there are something like 39 examples.

Leviticus “you shall love the stranger as yourself.

Numbers There shall be one law for you, whether stranger or citizen of the country.” [I think of the first section of the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which promises due process and equal protection for every person, not only every citizen]

Deuterotomy: You stand this day, all of you, before the Lord your God….even the stranger within your camp…

At this moment, when the world is again flooded with refugees, when our own nation closes its borders against the stranger, separates hundreds of children from their unfindable parents, when we have barred the gates to desperate refugees, when all those people who after the Holocaust said Never Again ignore the deaths and torment of the Rohingya, these 39 comandments, though not among the Ten, shame our nation, our generation. The insurrectionists who polluted the U S Capitol on Wednesday are the same people who demand the building of walls.

I end with Abraham Joshua Heschel, honored by his words included in Mishkan T’filah

We are a people in whom the past endures

in whom the present is inconceivable without moments gone by.

The Exodus lasted a moment, a moment enduring forever

What happens once upon a time happens all the time.

#####