D’var by Frank Salomon for Chayei Sara

D’var on Chayei Sara (Gen.23:1-25:18)

- A historical view (N. Sarna, R. Plaut):

According to the source-critical approach, Chayei Sara contains three segments:

First, a P or Priestly passage (23:1-20): Abraham’s purchase of Sarah’s burial place at Machpelah in Kiryat Arba (later Hebron).

Second (24:1-67), the mission to find Abraham’s perfect daughter-in-law, ending in Rebekah’s marriage to Isaac.

Third, a genealogy of Abraham’s descendants (25:1-18). The E version tells the Arab lineages from Abraham’s wife Keturah. P then summarizes the Hebrew family from Sarah, and other Arab lineages from Hagar.

This last shows how time fulfilled God’s promise that Abraham would become the father of many nations – not all friends.

Wrapping up, v.25:7-11, the P source leaps ahead momentarily to the burial of Abraham at Machpelah, which will actually occur in the main narrative 35 years after Rebecca and Isaac married. The Torah says nothing about these last 35 years of Abraham’s life.

Unusually for patriarchal history, Chayei Sara concerns a couple who turned out to be monogamous. Of course this has nothing to do with any program of monogamy. Nonetheless it does brings forward the idea that marriage creates an intimate relationship, just as central as the mother-son bond. The Chabad commentary mentions that this is the first time in the Bible that love is mentioned as an attribute of marriage, alluding to Gen.24:67: “Isaac then brought her [Rebekah] in to the tent of his mother Sarah, and he took Rebekah as his wife. Isaac loved her, and thus found comfort after his mother’s death.” R. Plaut comments that this sounds like a reaffirmation of Genesis 2:24, “Man leaves his father and mother and clings to his wife.

Let’s turn for a moment to what the betrothal expedition suggested to the story-loving old Rabbis, and then return to historical interpretation. (The stories are from Ginzburg, Bialik compilations of aggada.)

- “Eliezer’s Mission” in Aggada [Ginzberg, Bialik]

Chayei Sara never tells us the name of the Servant who found Rebekah. All aggadot identifies him with Eliezer of Gen:15-2. Eliezer was a slave whom King Nimrod had given to the then-childless Abram. Abram thought Eliezer would become his heir, until God promised a son. Profuse storytelling grows around Eliezer, Abraham’s right hand man.

We’re talking about an outsider. (EJ*) Despite his Hebrew name Eliezer is a slave and a Canaanite. In one aggadic passage Abraham distrusted Eliezer because: “No truth among slaves” [Ginz. 131]. He had reason for distrust. As the first shadchan Eliezer had a terrible conflict of interest: he had hoped Abraham would choose one of Eliezer’s own daughters to wed Isaac [282]. Aggadic Abraham says, nix to that, because “thou art of the accursed race.”

Yet in Aggada Eliezer turns out to be a wonderful guy. Abraham’s indispensable outrider well deserves his name meaning ‘God’s Help.’ In fact he becomes a superhero of X-Men dimensions. In combat he is a lion. In the fight with the Sodomites “Eliezer alone remained with [Abraham], wherefore God…said… I shall invest him with the strength of the three hundred and eighteen men whose aid thou didst seek in vain” [93].

What’s more, Eliezer and his boss Abraham mysteriously foreknew and observed all the mitzvoth that had not even been revealed yet!

Later, after meeting Rebekah, when Eliezer came face-to-face with Laban, he assumed a “body double” likeness to Abraham, which confused Laban. Laban wanted to kill him, but “soon learnt that he would not be able to do much harm to a giant like Eliezer” [Ginz. 292].

So Laban instead tried to kill Eliezer with poison. But Eliezer saw it coming. On the pretext of not having finished his speech, he passed the poisoned plate to Laban’s father Bethuel, and the old man died. That explains why Laban and not Bethuel contracted Rebekah’s marriage.

When it was time to return to Beer-laha-roi, God endowed Eliezer with warp drive. A “seventeen days’ journey” took him only “three hours.” The party arrived in the Negev in “time for Minhah,” which Isaac happened to have just invented [Ginz.301]. After the marriage Sarah’s glory returned to the scene in the form of a cloud descending on Rebekah’s new home, reminiscent of the tabernacle. “And the gates of the tent were opened for the needy, wide and spacious as they had been during the lifetime of Sarah [G302].”

In a further aggada, “as a reward…Abraham set his bondman free. The curse resting upon Eliezer as upon all the descendants of Canaan, was transformed into a blessing.” Eliezer became a King, Bashan of Og. [EJ 6:619]. In the end God chose him as one of only nine who entered Paradise alive [Ginz. 307].

Back to the historical view of J content

Abraham was wise in the ways of a tribal society. He showed as much when he required Eliezer to swear on his master’s procreative organs that he would find a bride “in the land of his master’s birth.” The land of Abraham’s birth was faraway Mesopotamia. Abraham, then, was opting for a long-term strategy of reviving alliance with his long-unseen kinsfolk instead of making a local Canaanite alliance as a less visionary leader might have.

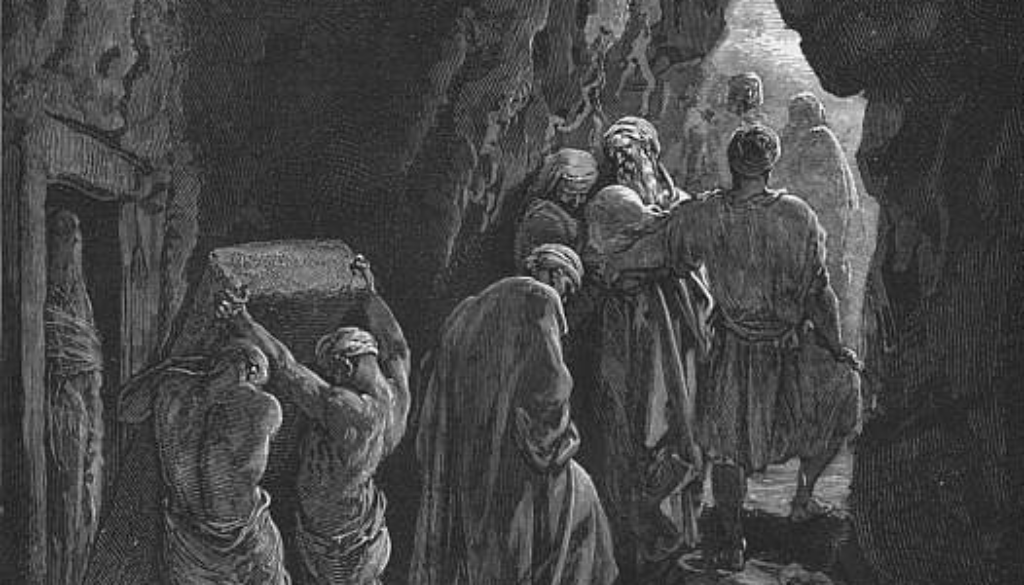

The Servant’s caravan went from the Negev to Nahor in Aram-naharaim, identified in the Targum as meaning “The Land within the River.” It is what archaeologists know as the Kingdom of Mittani in the Great Bend of the Euphrates (Sarna 163-64.) That’s something like 500 miles. No wonder the camels were thirsty!

(By the way, “Eliezer” brought ten camels. A camel drinks about 25 gallons. Picture 250 1-gallon jugs. “Rebekah hurrying down the steps of the well would have had to be a nonstop blur of motion in order to carry up all the water in her single jug” [Alter 120]).

One of the most artful things about Gen.24 is the Servant’s speech (24:34-52). It looks at first glance like a repetition of what was just told, and some commentators bring up repetition as a characteristic of oral literature. Robert Alter has a better explanation:

[When the Servant tells Laban what has happened, he] is careful to delete …all the monotheistic references to the God of heaven and earth and the covenantal promise to give the land to the seed of Abraham. Similarly excluded are Abraham’s allusion to having been taken by God …from the land of his birth – a notion the family [in Aram-naharaim] …might construe as downright offensive (Alter p.122).

In other words, part of the narrative tension comes from a problem greater than the distance from the Negev to the Euphrates: it is the cultural distance between the polytheistic Mesopotamian branches of the kindred back home, and the small splinter that Abraham has led away on his strange monotheistic quest.

Sarna thinks it’s fitting that J never tells us the Servant’s Name, because he never figures again. In respectful disagreement I think the Servant is the hero of the “J author’s masterpiece.” We owe a lot to Abraham’s decision to reach out to a pagan branch of his kindred. But the approach only worked out because the Servant handled that tricky encounter so intelligently and peacefully. (Peaceful, provided you can cut Eliezer some slack about poisoning Rebecca’s dad.)

In the end, though, the aggada leaves me sad. It treats Eliezer’s perfect loyalty to his master or slaveowner as marvelous. In the tribal ethos, it was. But pairing Eliezer’ self-abnegating loyalty with Rebecca’s engagement brings marriage and servitude uncomfortably close together. What Chayei Sara means, then, depends on what happened to Eliezer later on: ascent to paradise? Or the gruesome death of King Og? We don’t know — yet. We’ll have to make more Aggada.