Relishing the Road Ahead

The books of Genesis and Exodus often take the lime-light. They have all the good stuff: exciting narrative, fantastic plot devices and compelling character development. The stories of those two books of the Torah are the stuff of movie scripts.

By comparison, the books of Leviticus and Deuteronomy get the short shrift. We like to kvetch about Leviticus and its punctilious laws while Deuteronomy seems to feature a lot of lengthy (and dare I say, boring) speeches.

Of course, neither characterization is fair. There are stretches of legal and genealogical material in Genesis and Exodus that do not entice while there are great portions of narrative in Leviticus and Deuteronomy that speak to the timeless human imagination. Between these sits the book of Numbers, somewhere in between: part legal, part narrative material; brimming with tension, ambiguity and conflict.

Over the years, I’ve grown fonder of Numbers. Called ‘Bamidbar’ or ‘in the wilderness’ in Hebrew, there is something untamed about its stories. This is the book in which the Israelites become unhinged. Complaint follows complaint, rebellion follows rebellion. It’s a brilliant study of human nature and group dynamics. In Parashat Beha’a lot’cha, we are starting to see the cracks: Moses, Aaron and Miram argue; the Israelites demand meat instead of manna. Yitro (identified by another name in the portion) leaves to return to his own land. Miriam falls ill and is close to death. And this is just in one Parashah! Over the next few weeks, we are going to see more troublesome dynamics: the scouts are sent out but bring back a negative report and Korach’s rebellion is fomented. In true soap opera fashion, it gets worse. Two parshiyot on, in Parashat Chukat, Miriam dies, Moses is punished for striking the rock at Meribah instead of talking to it and Aaron also perishes. Next up is the murderous zealotry of Pinchas.

A lot happens in this book. At times, it can feel disjointed and unclear as the narrative weaves in law and alternates between condemnation and despair. As Rabbi Shai Held writes in his ‘The Heart of Torah’ compendium:

There is something profoundly tragic about the book of Numbers. A people liberated from slavery, protected by a faithful God, and promised a good life in a land flowing with milk and honey simply cannot overcome its fears, its lack of faith, and its inability to trust. Instead of journeying forward, it looks backward again and again, grumbling and complaining, longing for Egypt, and eventually succumbing – again – to the lure of idolatry. What should have been a story of a triumphant march to the Promised Land becomes something else entirely—a dreadful tale of distrust, disloyalty, disappointment, and ultimately, death.

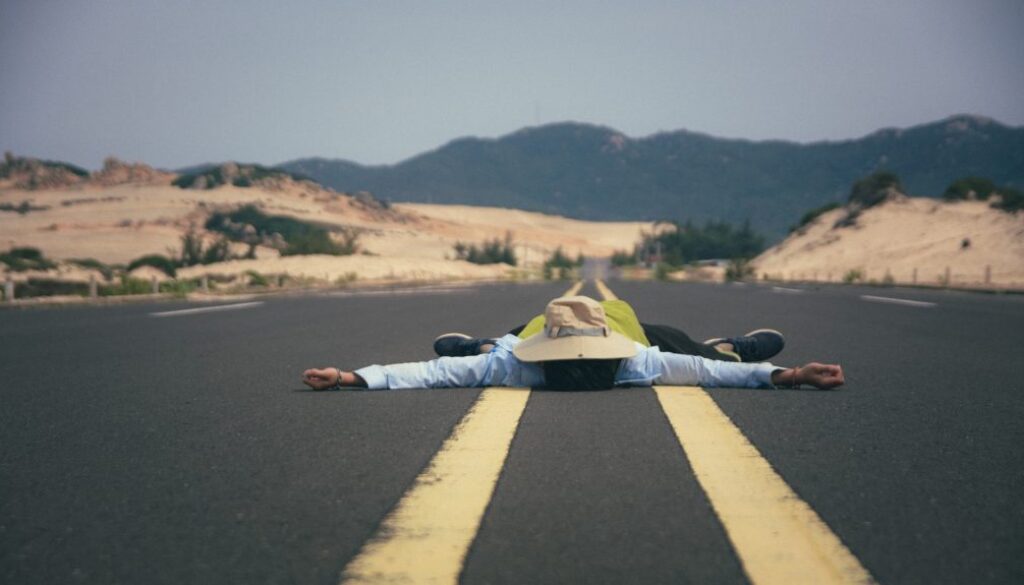

This is true, of course, and as the Torah does often, can hold up a mirror to our own lives. When are the moments we have felt rebellious, desperate and cynical? Sometimes we may feel that life is quite the trip – or the Road Trip from Hell. The tragedy of Numbers is that of human frailty. The Israelites, and by metaphorical extension, any and all of us, keep on making the same mistakes. It is the human condition stuck in a rut.

is easy for any of us to experience jealousy, power struggles, leadership anxieties, fear of the unknown, temptation, anger, impatience and greed. We expect the Israelites to overcome this last final hurdle – entry into the Promised Land – and yet, we are confronted with an existential angst that ‘we are grasshoppers in the eyes of giants, and in our own eyes also’.

This place of vulnerability is also one of growth. There’s a poignant moment in this week’s Parashah where Moses pleads with his father-in-law to stay. We know that his father-in-law accompanied him early on in the book of Exodus. He has lent Moses important counsel. But now, he wishes to return. The Torah tells us:

Moses said to Hobab son of Reuel the Midianite, Moses’ father-in-law, “We are setting out for the place of which the Eternal has said, ‘I will give it to you.’ Come with us and we will be generous with you; for the Eternal has promised to be generous to Israel.” (Num. 10:29)

Moses’ vulnerability is moving; what the tradition characterizes as his ‘anivut’, his humility. He has the insight to know that he needs all the help he can get. He has grown emotionally attached to Yitro (called here by another name). ‘L’cha otanu’, ‘come with us’, he says, in a scene that has some future echo of Ruth the Moabite and Naomi, her mother-in-law. Yet, such is life that Moses’ request is turned down and his beloved father-in-law returns to Midian, in wording that echo the past journey of Abraham, but in the reverse: ‘ki im el artzi v’el moladeti elech’, ‘for I will return to my land and to the place of my birth, I will go’. Moses pleads; he wants him as his guide.

Perhaps this rejection sends Moses into a tailspin. But Yitro’s decision makes sense: Moses now has to manage in his own way. If anything, the book of Numbers is a commentary on our journey through life and the cultivation of maturity and resilience. And it is in this that the narrative offers us hope.

For every crisis that Numbers recounts, there is opportunity. This Parashah alone is brimming with solutions; with empowerment and healing. At the depth of Moses’ despair, where he fears his sister’s death, he haltingly prays ‘El na refa na lah’, ‘God, please, heal her, please’. Miriam is healed and through the solidarity of her community who stand with her, reintegrated and redeemed.

Numbers is a Rorschach test. We can identify moments of profound instability, or periods of genuine growth. The difference between the two states is whether we can identify the tools that the Torah gives us. Hope, t’shuvah, reconciliation, growth, self-examination, resilience, trust. While Numbers acknowledges the pain and loss of transformation (the entire wilderness generation dies), it also invites grace. As Rabbi Held writes:

Yet according to the Torah, God’s love and faithfulness do not readily accept defeat. And so even amid sorrow and devastation, old-new possibilities emerge. Despite everything, Numbers urges, Gods hopes and promises will yet be fulfilled… The reader of Numbers is invited to imagine him- or herself as part of a new generation poised to enter the Promised Land. Will we see only what seems impossible and thus spurn God and the possibility of genuine faith? Or will we trust in God, and thereby discover the hope and possibility that God continues to make possible?

However we experience God’s presence; as we continue on our own life’s journeys, let that word ‘possible’ be our lodestar; let these values be the formation in which we march. It is not for naught that Numbers is read between Shavu’ot and Tisha b’Av, stretching all the way to the High Holidays. Journeys are hard. Yet we can say to God and to each other: ‘l’cha otanu’, ‘come with us’. We undertake them, individually yet not alone and are forever changed.

May we relish what the road may bring.